***

This piece is a contribution to the STSC Symposium, a monthly set-theme collaboration between STSC writers. The topic for this issue is “Work.”

***

Seagram Building, Park Avenue, New York City, 1959: outside, the church bells toll nine o’clock, and a few dozen employees enter the office, busily and noisily. One hurriedly removes her walking shoes and retrieves high heels from her desk drawer. Another ungracefully adjusts her panty hose. Yet another removes her curlers. Pencils are sharpened and lunches are placed in the refrigerator. It is a women’s—I mean, girls’—space.

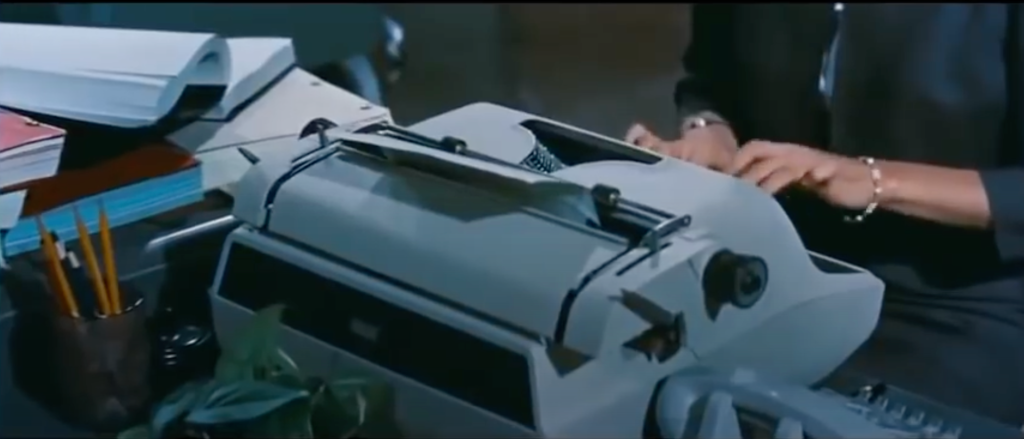

In time the chatter and bustle give way to the sound of four hundred fingers tapping. There are neat, orderly rows of typewriters, each emitting an identical sound, multiplied again and again to make a noise like a cloud of cicadas. It is the sound of well-regulated labor and clearly assigned roles: individual keys clacking, each letter leading to a word, then a sentence, then a paragraph. The secretaries render the thoughts of other people in impersonal black and white. The thoughts of other people. They are the helpers, the empty vessels.1

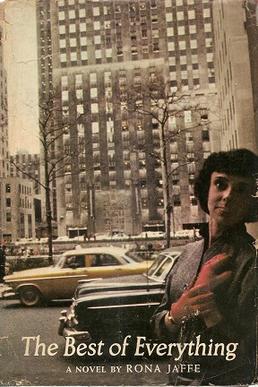

Jean Negulesco’s 1959 film The Best of Everything, based on the 1958 novel of the same name by Rona Jaffe, focuses on the experiences of several young female secretaries in the New York City publishing world.2 Jaffe took her title from an advertisement in the New York Times, a replica of which is shown in the film. But that titular “everything” will prove elusive, as the trailer for the film predicts:

In the outspoken tradition of “Peyton Place”, 20th Century-Fox brings a great best-seller to the screen . . .

It undresses the ambitions and emotions of the girls who invade the glamour world of the big city, seeking success, love, marriage, and the best of everything . . . And who often settle for much less!3

Along with the advertisement, this text signals that a “women’s picture” will follow, and that the conflict between professional work and romantic love—between “hearth and desk”—will prove central.4 An alternative, less sensationalistic trailer might ask, “Will she type his manuscripts . . . or make him a sandwich?”

The conspicuous use of the word “invade” may suggest something about how these girls will be received in the working world, as well as by viewers of the film. Contemporary critical responses to the novel betray the unease created by such an intrusion. For example, the New York Post advises, “Any employer reading these pages will make a mental note to check up on what the girls in his office do after lunch, and with whom.”5

“Girls”: this terminology is of course typical of the time period, and I shall adopt it in this essay in order to evoke the setting of The Best of Everything. In 1958, the employer is assumed to be a man, and by default the supervisor of any girls who happen to be frolicking about and getting up to shenanigans. Comments from the time reveal a disquiet about young professional women. For example, New York Times critic Gilbert Millstein is palpably perturbed by Jaffe’s novel. At the outset of his review, he dismisses The Best of Everything as a “pallid academic exercise.” However, he goes right on to complain about its commercial success: the novel was optioned by the producer of the popular 1957 film Peyton Place, Jerry Wald. Millstein expresses apparent resentment over Jaffe’s earnings ($100,000 for the film rights and $25,000 for the paperback reprint of the novel) and gripes that the “attractive-looking girl of 26 obligingly, possibly eagerly” posed for the book’s cover at “the Forty-ninth Street side of the Time-Life Building.” (How dare this attractive-looking girl of 26 profit from her labor and be eager at the Time-Life Building to boot?!) Millstein’s “this-is-so-worthless-I-must-catalogue-every-feature-of-it-to-show-you-how-worthless-it-is” comes across like a 1950s Tweetstorm. He mocks the title (might its reference to the Times Help Wanted advertisement entail “copyright infringement”?) and condemns the story’s “verismilitude,” comparing it to a Norman Rockwell magazine cover. He sneers, “The book could easily have been called “The Five Little Peppers in Rockefeller Center, or ‘Little Women, What Now?’”6 This response to the novel displays the same fears and resentments that the author depicts in the novel. Inside and outside the covers, career girls evoke terror in the hearts of (not all) men.

It is not only critics who place female characters in a double bind. The characters do so as well. At a critical point in the film, the pressure on a girl to embrace domesticity and humility—and even to efface herself intellectually—comes to a head. A male executive, Mike (Stephen Boyd), insists to the much younger Caroline (Hope Lange), with whom he has already shared a couple of intimate moments, that it is unseemly for her to prioritize her work, for she will become a “ruthless, driving, calculating woman.” More, he claims that her commitment to her vocation is false and insincere: “Honey, you don’t give a damn about your work. All you care about is your own hot-eyed ambition.” The opposition between “caring” and “ambition” reveals just how confining social expectations are: a compliant girl is required to “care,” which is assumed to be incompatible with professional drive. According to Mike, Caroline’s ambition allows her to hide from her grief over the end of a relationship, and her desire to succeed professionally is even incompatible with womanhood: “Now you’ve closed the door. Being a woman is too painful, so you’re not gonna be one. Men aren’t lovers; they’re competition, so let’s not join ‘em; let’s lick ‘em.”

However, it is the men in the workplace who do the majority of the licking. The editor Mr. Shalimar (Brian Aherne) pinches, slaps, leers, and smirks his way through the film. Yet according to the New York Times, it is the girls who have “a nose for trouble,” and sex “seems to be all these ingénues have on their busy little minds.”7 In many commentaries from the time, the younger and lower-status girls are held responsible for what is on their superiors’ minds, and for what they do with their hands. In keeping with the conventions of the women’s picture, the male love interests from outside the company, often closer to the girls’ ages, are also unscrupulous cads. This is not merely an interpretation applied from sixty years later; it was was understood by viewers at the time and was even acknowledged by the characters. The womanizing theater director describes himself as a “heel,” and the thoughtless playboy who has duped the naïve, pregnant April (Diane Baker) into “seeing a doctor” admits, “I know what I am.” Another heel, presumably.

As above, a comparison of the ways social mores are portrayed within the story and the ways they are asserted in the discussion about the novel and the film proves fruitful. Commentaries from the time come across like dispatches from the proverbial six blind men describing the elephant. Some find the story authentic; others condemn it as tawdry; and yet others yawn, “how unstimulating.” A sensationalistic soap opera bores many a critic, and the girls are alternately lovelorn or obsessive. Unsurprisingly, reviewers of the 1950s did not distinguish between a young male peer tentatively caressing a girl’s knee on a date and a workplace superior reaching under the table to push up a subordinate’s skirt as he dangles professional advancement in front of her. The film, like the novel, is remarkable in making this distinction, and I would suggest that this accounts in large part for the jumbled responses of the late 1950s. In recent years, Jaffe’s novel has been credited for breaking ground in portraying sexual harassment. As she says,”sexual harassment . . . had no name in those days.”8 The sexualization of the relationship between male superior and female secretary was pervasive and unquestioned—the water the girls and men swam in.9

The New York Times connects the girls’ adventures and misadventures directly to the typewriter, even invoking several inventors of the device: “Little did Messrs. Sholes, Glidden and Soulé know, when they invented an American typewriter, what a power of mischief it would bring. . . . The girls come to New York to type, and before long, one is a stretcher case, one is pregnant and the third is off to Las Vegas with a notorious lounge lizard.”11 That licentious machine, causing so much drama!

Back at the desk with the sexy IBM Selectric, her finger presses a key, which delivers a hammer to a ribbon and marks paper. Thousands of characters are impressed onto hundreds of pages. Seventy words a minute times forty girls equals piles of edited chapters, reader’s reports, and rejection letters. Thanks to the standardization granted by the machine, the page bears no trace of the individual hand. The typed text is as orderly and regular as the rows of secretaries’ desks. The individual girls are a collective serving the purpose of the corporation: they are indistinct and undifferentiated.

But what happens when a girl leaves the typing room? Again and again throughout the film, a secretary enters a private office, then closes the door, thereby silencing the typewriters. The sound design emphasizes the movement from public to private in a way the printed words on the page of the novel cannot. Early in the film, Caroline enters Miss Farrow’s (Joan Crawford) office and closes the door. The typewriter sounds disappear abruptly. This contrast suggests a difference in role and rank: it is in these quieter, more spacious rooms that the editors do their heavy thinking and prepare materials for the girls to type.12 Alone with Miss Farrow, away from the group, Caroline is subjected to a hazing ritual, as Miss Farrow gives her several tasks in rapid succession:

“You can order me some coffee: black, no sugar. . . . No, no, no, at your desk, outside. Before you do that, would you straighten out the files? The Ts have gotten all mixed up with the Ms somehow. . . . You can do that later. Open the mail first.”

It’s not that Miss Farrow is respectful in the outer office; she’s merciless, but in the group environment outside Caroline has coworkers—allies who witness and empathize. When she enters Miss Farrow’s office, she is confined with her tormenter, with no witnesses on hand.

If Miss Farrow’s office proves an Ironman course for Caroline, the men’s private offices are where they play Twister. In numerous instances, a male executive invites a female subordinate into his office, suggesting that there is important work to do, only to make a move on her. The private, quiet environment is a place of sexual dominance. This is most striking when the gullible girl, April, works late with Mr. Shalimar. He offers her alcohol, asks her personal questions, and pounces. On another occasion, Caroline is called in by Mr. Shalimar. He chooses to tell her she has been promoted by saying, “You are no longer a typist here,” a cheap trick that exploits his power. In a previous scene Caroline has had to extricate herself from his grasp; this time, when she departs, Mr. Shalimar cranes his neck and leers at her body with appreciation. Throughout the course of the film, the repeated appearance and disappearance of typing sounds supports the portrayals of the individual characters, their development (or not), and the relationships between them. It is as important a sonic feature as the musical score.13

So, while The Best of Everything is understood to show conflict between romantic yearnings and professional drive, there is also a conflict between personal and professional right here in the office. Or, more accurately, between professional and unprofessional. To the girl like Caroline who aspires to perform substantive work and achieve higher rank, the door to the private office represents her potential status. But that same boundary also signifies risk for every girl, any time she is required to interact with a superior in private. It is not only that the girls have to choose between love and work, but that at work they are disturbed by influential men who behave as if they are their own living rooms, not in a workplace.14 The girls are constantly sexualized by others, whether they like it or not. The quiet and space of the executive office promise stimulation, independence, position—as well as danger and dehumanization.

The lack of young men in the office is easy to overlook but significant. Mulling the way that professional power maps on to age difference and onto sex, I think back to a brief, atypical moment just a few minutes into the film. Caroline enters Fabian Publishing and finds it empty, save for a man delivering mail. He is closer to Caroline’s age than anyone else she later meets at work, and he is dressed more casually: a shirt and tie, but no suit jacket. His hands are busy with work. He and Caroline exchange a few words, and he informally asks, as if it’s one word, “first day first job?” When she asks how he knew, he replies, “the hat,” wishes her luck, salutes her, and exits. This easy interaction between young adult coworkers stands out, for once the office fills up and Caroline begins her first day, she never encounters another young male peer. One wonders what Caroline’s work day would be like if the men were not all older and more powerful, if the one mature woman were not repeatedly called a “witch,” and if the “lovelorn” girls were recognized as working women.15 Maybe someday. In the meantime, it’s a great hat.

Notes

[1] “Under the Isaac Pitman [shorthand] regime, the ideal typist was trained to be blind and invisible, as it were, a passive mediator who was effectively mentally absent from the task in which she was engaged. The prevailing discourse of female passivity vis-à-vis the machine becomes fully legible only in the context of such instructions to the typist to completely efface herself from her own work process.” (Martyn Lyons, The Typewriter Century: A Cultural History of Writing Practices [Studies in Book and Print Culture]. Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 2021 [p. 65, Kindle Edition].)

[2] Rona Jaffe, The Best of Everything (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1958). The film was produced by Jerry Wald with a screenplay by Edith Sommer and Mann Rubin and music by Alfred Newman. The novel was written expressly to be made into a film. In her foreword to the 2005 edition of the novel, Rona Jaffe reports, “One day, I was visiting the offices of Simon & Schuster to see my college friend, Phyllis Levy, who was then secretary to the editor-in-chief, Jack Goodman. Jerry Wald, the famous Hollywood producer, happened the be there meeting with her boss.” Wald was “scouting for properties to option,” and he later agreed to produce the novel Jaffe promised to write (Rona Jaffe, The Best of Everything [New York: Penguin, 2005]). Because the novel and film were so closely associated—not to say the same—I rely on reviews of the novel as well as the film.

[3] The trailer continues:

THE GREAT BEST-SELLING STORY of . . .

THE GIRLS WHO WOULD DO ANYTHING TO GET . . .

“THE BEST OF EVERYTHING.”

The contradiction between “settling” and “doing anything” to get what they want is characteristic of the ambivalent view of women in the reception of the film. The Best of Everything: Official Trailer (20th Century Fox, Klokline Cinema).

[4] I adopt the terms “hearth” and “desk” from Bosley Crowtherhoward Thompson’s film review: “Screen: Frustrations in Young Actor’s ‘Career’; Franciosa Is Star of New Film at State James Lee’s Play Is Story of ‘Disease’.” The section on The Best of Everything comes under the subheading “Office Romances.” New York Times, Oct. 9, 1959, p. 24.

[5] Review from 1958, excerpted in the front matter to the 2005 edition of Jaffe’s The Best of Everything.

[6] Gilbert Millstein, “Books of the Times,” New York Times, September 9, 1958, p. 33. Several of the 1958 reviews excerpted in the 2005 edition of the novel praise its authenticity; perhaps this is what Millstein belittles as “verismilitude.”

[7] Review of Jaffe’s novel by Martin Levin, “Three Noses for Trouble” (New York Times, Section BR, p. 38; September 7, 1958).

Martyn Lyons observes, “The Typewriter Girl caused anxiety, especially for employers. Would she cope physically with the demands of the job? Was she capable of the hard work, discipline, and concentration required? If so, would she lose her feminine qualities in the process, becoming as hard and ‘de-sexed’ as the machine to which she was invisibly bonded? And furthermore, what effect would she have on the men in the office? Would she distract or seduce them? The typewriter entered a highly eroticized environment, in which forms of sexual harassment of the typist were potentially more likely to disrupt operations than ‘distracting the men’.” (Lyons, Martyn. The Typewriter Century: A Cultural History of Writing Practices [Studies in Book and Print Culture]. Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, p. 57 of Kindle Edition.)

[8] Jaffe’s recollection confirms the supposition that readers literally did not have the language for the girls’ experience at the time: “Back then,” she writes, “people didn’t talk about not being a virgin. They didn’t talk about going out with married men. They didn’t talk about abortion. They didn’t talk about sexual harassment, which had no name in those days. But after interviewing these women [as research for the novel], I realized that all these issues were part of their lives too.” (Jaffe, Foreword to 2005 edition, viii.)

[9] Carol Burnett’s 1975 sketch “The Other Secretary” takes on the competition between secretary and wife: “You’ve been taking his dictation, haven’t you? Haven’t you?! How long has he been giving it to you?!” (Carol Burnett Show, Season 8, Episode 15.)

[10] This image of Sholes (1819 – 1890) is included in The Story of the Typewriter: 1873-1923 (Herkimer , NY: Herkimer County Historical Society, 1923), which was published on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the invention of the typewriter. The cover of the publication displays another striking image of a goddess-like woman towering over a city and laborers holding a divine typewriter. Like other sources, this volume asserts that the typewriter offered economic advantage to women. Chapter 8, “How Women Achieved Economic Emancipation Through the Writing Machine,” notes,

The movement that we know by the name of “feminism” is undoubtedly the most significant and important social evolution of our time. The aims and aspirations behind this great movement need not detain us. Suffice it is to say that, like all great social movements, its cause and its aim have been primarily economic. What is known as “sex-emancipation” might almost be translated to read “economic emancipation”; at any rate it could only be attained through one means, namely, equal economic opportunity, and such opportunity could never have been won by mere statute or enactment. Before the aims of “feminism” could be achieved it was necessary that women should find and make this opportunity, and they found it in the writing machine.

[11] Martin Levin, “Three Noses for Trouble.”

[12] In Rona Jaffe’s novel, the hierarchy is demonstrated explicitly, in the moment when Caroline explores the office before anyone else arrives: “She looked into several of the offices and saw that they seemed to progress in order of the occupant’s importance from small tile-floored cubicles with two desks, to larger ones with one desk, and finally to two large offices with carpet on the floor, leather lounging chairs, and wood-paneled walls” (Jaffe, Everything, 2005 edition, p. 2).

[13] There is much more to say about sound in this film. The score includes an opening song by Alfred Newman with lyrics by Sammy Cahn and performed by Johnny Mathis, which is repeated and varied in instrumental settings throughout the film. The mix of the score, the carefully controlled typing-pool sounds, and the diegetic sounds of the city complicates the presentation of the love/labor conflict.

The “typing track” and its alternation with silence is used cannily to show both Caroline’s ascent and the softening of Miss Farrow’s attitude. It also replicates the male/female division on another level: while the girls are subject to sexualization from their male superiors, their female superior (Miss Farrow) refers, every time she is in private with one of the secretaries, to the status of women or the relations between men and women, albeit not necessarily in a benign way. Both she and Caroline, in different ways, show the change in their relationships to male executives when the typewriters are quiet and they are in private. Both are portrayed sympathetically; neither is idealized.

[14] In Mike’s first appearance, he disrupts Caroline’s work. He enters the office, drinks from the water fountain (to treat his daily hangover, we will quickly learn), stops, and stares silently at Caroline as she undergoes her typing test. She is intruded upon as she completes the test that will determine whether or not she is hired.

[15] “In a lovelorn typing pool, ambitious Caroline (Hope Lange), innocent April (Diane Baker), and glamorous Gregg (early supermodel Suzy Parker) are all felled by the cads they love. The movie is about as sexist as you can get on both sides, to an almost absurd (and campy) level: There’s only one exception to a parade of male leads who may or may not be married and are just out to get a little action on the side.” (Gwen Inhat, “The Best Of Everything Offers a Valuable Glance at Postwar Office Romance,” AV Club, July 29, 2016.)